Truth and reconciliation in sports

📚 The history

It’s no secret that the history of North America is woven with atrocities against Native peoples. Prior to European colonizers arriving in the Americas, there were an estimated 60 million Indigenous people living across the two continents. Due to genocide and disease, that population dwindled by 90% to 6 million in about 100 years.

Harm of Indigenous communities did not stop there. For centuries, policies and practices in both the U.S. and Canada displaced Indigenous people and sought to eradicate Indigenous culture. And one way they did so was through residential schools.

- These government-mandated schools were central to the mission to “assimilate” the Indigenous population. Children were removed from their families and communities under the auspices of “civilizing” Native peoples. Horrifying.

- The first Canadian residential school opened in January 1831 and the U.S. followed suit in 1879. These boarding schools existed in both countries well into the 20th century, affecting hundreds of thousands of children.

- Besides the loss of culture, language, spiritual beliefs, community and even their names, Indigeous children often suffered abuse, and many never returned home. Both Canada and the U.S. have recently discovered mass burial sites at residential schools.

In response to its dark history, Canada established Truth and Reconciliation Day in 2021. In the same year, President Biden declared the second Monday in October as Indigenous Peoples’ Day, officially recognizing the holiday that began in 1977. Small, but necessary steps.

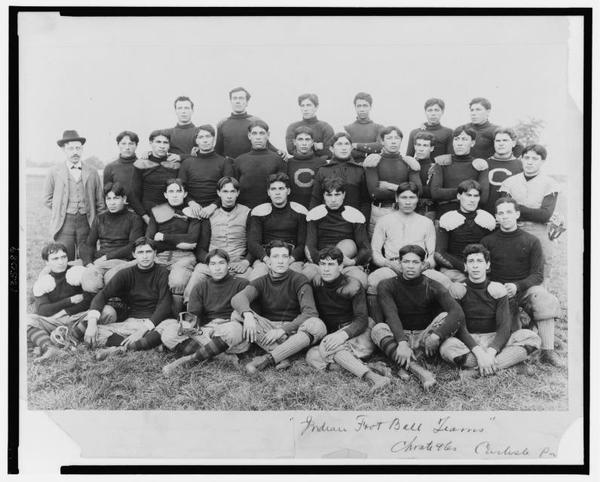

🏒 Sports in residential schools

Today, many survivors of residential schools cite sports as their key to survival. Amid violence and abuse, Indigenous children found respite in sports and, in Canada, most often on the ice.

- Eugene Arcand, a First Nations residential school survivor who played semi-pro hockey, describes sports as his “safe space.”

But while sports were helpful escapes from the horrors of boarding schools, they were also used as tools for assimilation. The use of hockey at Canadian residential institutions, for instance, served to indoctrinate the students into seeing themselves more as “Canadian” than as Indigenous.

- Schools often banned or discouraged Indigenous sports, like lacrosse, to separate children from their culture and emphasized winning over other more important Indigenous values, like community.

And for girls, the indoctrination went a step further. Schools were often segregated by gender, and (stop us if you’ve heard this one before) girls were barred or discouraged from participation in sports. Instead, they were pushed into knitting, cooking or cleaning in an effort to represent more Euro-centric gender roles.

💪 Trailblazers

In spite of multiple barriers to participation, Indigenous athletes have been overcoming obstacles and setting standards across North American sports for over a century.

One of the GOATs of the sporting world, Jim Thorpe, was near-limitless. The Sac and Fox Nation member took Olympic gold for Team USA in both the decathlon and pentathlon in 1912, played six seasons in MLB and became a pro football Hall of Famer. Legend.

Another Olympian that (literally) blazed trails is Billy Mills. The Oglala Lakota track star ran the marathon and the 10K race at the 1964 Tokyo Games, becoming the only American to ever win 10K gold when he broke the Olympic record with a time of 28:24.4.

After being introduced to cross-country skiing by a government program for Indigenous youth in the 1960s, Gwich’in First Nation twins Sharon and Shirley Firth suited up for Team Canada at the 1972 Olympics, becoming the first Indigenous women to compete for the country. Together, they netted 79 (!!!) medals for Canada across their skiing careers. Damn.

Canada’s Waneek Horn-Miller may be the embodiment of Indigenous resilience. At just 14, the water polo star was stabbed within a centimeter of her heart by a Canadian soldier’s bayonet during a violent land dispute in 1990.

- The Mohawk woman recovered, helping Canada to Pan American gold in 1999 and co-captaining the country’s first-ever women’s Olympic water polo team in 2000.

🔮 The present and the future

Today, Indigenous athletes are changing the sports world. With players like the NHL’s Carey Price (Ulkatcho First Nation), the NBA’s Kyrie Irving (Standing Rock Sioux), the Premier Lacrosse League’s Lyle Thompson (Onondaga Nation) and NCAA volleyball player Emoni Bush (Wei Wai Kum First Nation), Indigenous athletes have more vital representation across sports than ever before. We love to see it.

And these athletes are also speaking out. The first Native American in pro women’s soccer, Angel City FC’s Madison Hammond, recently called out NJ/NY Gotham FC captain McCall Zerboni for using racist lexicon that disrespects Indigenous culture. The Navajo and Pueblo defender used her voice to educate more than just her fellow players.

In reclaiming their past, Indigenous athletes are laying the groundwork for the future. Indigenous players are systematically redefining the game of lacrosse, which could make its way back into the Olympics in 2028 after a 120-year absence.

- The Haudenosaunee have their sticks up not just for the sport’s growth, but also for official recognition of their nationhood by the International Olympic Committee, so they can compete under their own flag.

- Player Brendan Bomberry summed it up in his pep talk to his Haudenosaunee National teammates before this summer’s World Games: “Sports may not be political, but for our people, they are.”

Enjoying this article? Want more?

Sign up for The GIST and receive the latest sports news straight to your inbox three times a week.